Paul Salopek walks.

It’s an admirable hobby, and one that I aspire to persevere in as I decline, though various aches and pains signal a staid future of virtual strolling through the metaverse (previously known, in a more muscular era, as “surfing” the internet) is on my horizon.

I digress. Salopek has been trekking “Out of Eden” for over a decade, tracing the migration routes of our shared human ancestors, and documenting his experiences at National Geographic. National Public Radioheads may have heard him describe this 38,000 kilometer journey as a frequent guest on The World.

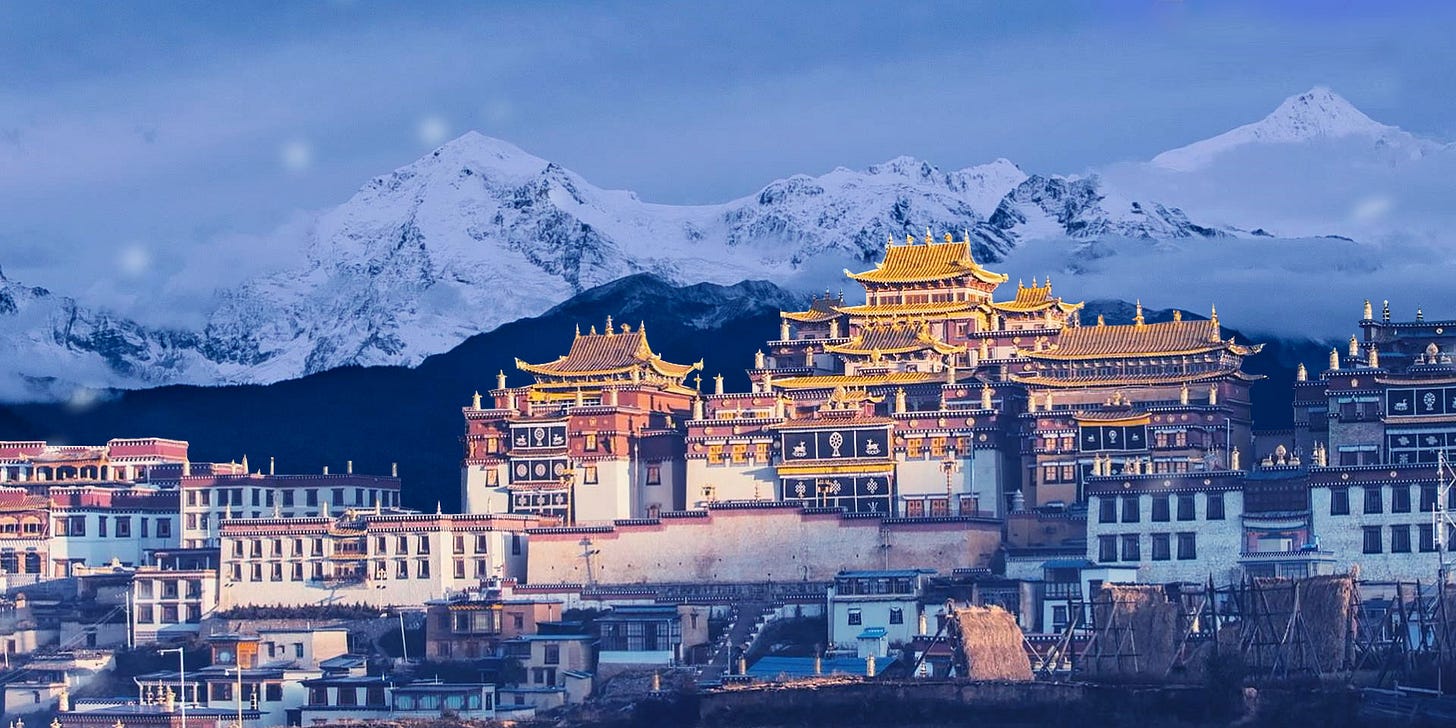

Recently, he visited the city of Yunnan, China, where he regaled his followers with tales of the Bai, a minority ethnic group in southwestern China, that numbers just 2 million souls. What is remarkable about the Bai, other than the jaw-dropping backdrops of their region, is their use of song to communicate.

Salopek chatted up a community leader named Li Gen Fan, who explained the central role of lyricism in his village:

“We’re kind of shy, introverted people. We don’t really communicate very well, kind of verbally, you know, but through conversation. But we get our emotions out through song.”

This story about the Bai captures an essential feature of the hybrid fiction of Benjamin Labatut and W.G. Sebald, who have pitched their stakes around the sliver of literary fictional territory that I endeavor to squat on.

Fiction, like song for the shy denizens of Li’s village, is just another form of communication about the world. It can grapple with certain truths about the world that are too big to be expressed in ordinary, matter-of-fact, non-fictional prose.

Now, the resolution of the constraints of ordinary non-fiction might achieved through ordinary fiction. Fiction need have no boundaries (which is not to say that it does not). One can be as pedestrian or outrageously fantastical as one wants. If one feels incarcerated by objectivity, with its harsh palette of senseless ambiguities and undeveloped non-heros, it is easy enough to fictionalize.

Yet the fiction of Labatut and Sebald aspires to something else, to a world beyond the duality of fiction and non-fiction. So too does Just Dicta. The book seeks a unique manner of singing about the world that draws liberally on the registers of both non-fiction and fiction, of what it means to report on objective fact and what it means to see beyond the walls. It aims, in short, to complicate boundaries between objects that we consider distinct, and particularly, between and among our ideas about truth and morality.

That is why, unless you are a constitutional lawyer, or I have executed my plans poorly (a distinct possibility, to be sure), you will likely not be able to distinguish between fictional and non-fictional text in the judicial opinions in Just Dicta. By design, the legal fiction is parasitic on the non-fictional language and style of the courts. I chose to shackle myself with non-fictional conventions, while also partaking of the liberties of the novel. Some form of hand-binding is often a point of departure for novel thought: the point of much art is to lattice creativity around convention. “No rules” often means nothing of value (in any genre).

If partial fictionalization of judicial opinions is core to the work, the book also tests the boundaries of fiction and non-fiction in other ways, drawing on a great deal of scientific and philosophical work. Straight non-fictional artifacts (a coroner’s report, an academic abstract) are deployed to augment the plausibility and depth of fictional events, particularly as they relate to judicial process, while also challenging our sense of what is real, and where the line should be drawn between genres.

But why focus my lens on the law?

Writing in this way allowed me to test the limits of the literary framework and rationality of the courts. If the Supreme Court is, as John Rawls thought, the “exemplar of public reason,” and the courts are our best shot at rational deliberation in a democratic society, what happens if we extend their style and forms of thought to novel scenarios? How do they weather the exposure? Do they still sing to us, or do they collapse under their own contradictions when taken to their logical, but imagined, conclusions? Does human reason triumph or disintegrate when it is stretched?

Why do I say “literary framework” and not simply rationality? Why does the literary content of a judicial opinion matter? One might say (and I am sure someone has) that literary tropes and sly turns of phrase are “just dicta” and have no meaningful place in a well-ordered society based on the rule of law and public reason.

I respectfully dissent.

Writing is thinking. The literary style and form of judicial opinions is a particular way of communicating ideas and structuring thought. That style might facilitate our understanding of the truth, and of the good, or it might distract us. Style has aesthetic value and needs no further justification. But the value of style does not end with aesthetics.

Singing is not merely speaking elliptically with background music. Just as the Bai idiom “I love you with all of my liver” does not mean the same thing as “I love you with all of my heart.” They share a common thrust, but they contain other multitudes.